The Half of the Animal We Don’t Eat

by ryan heeney / February 7th, 2024

A common word in the health community for some time now has been "refined." Refined junk food, refined carbohydrates, refined sugars, etc. Well, another "refined" food is just as common and just as regularly consumed but hardly ever got mentioned. What could this "refined" food be, you might ask?

Well, weirdly enough, it's meat.

There are those who swear meat will kill you and those who think it's the healthiest food on the planet. I believe the answer is probably somewhere in between and depends heavily on context and how meat is actually consumed.

Before we begin delving into the potential positives and negatives of eating meat, I want to be clear that this article will explore the topic from a scientific, unbiased point of view. This topic is not to diminish those who feel motivated in not eating animals for ethical reasons; which some of those issues deserve attention and a spotlight (especially because of the conditions of many factory farms today). This article explores this topic purely through the lens of nutrition and its effects on health.

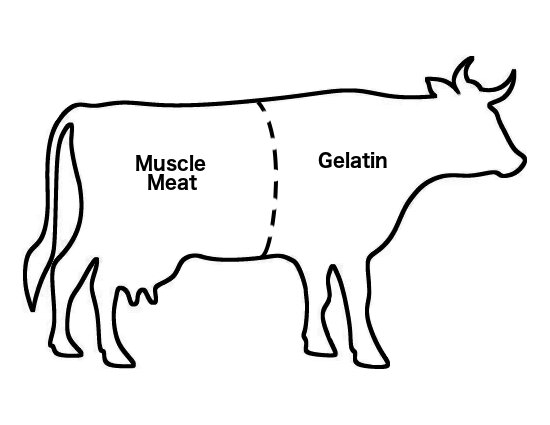

The best place to start is to be aware of the general protein composition of the animal first. On average, the total protein content that makes up an animal is roughly half from muscle meat and half from collagen. Muscle meats are all the cuts of meat we are familiar with in Western culture. Since beef is so often consumed, we will use the steer as an example.

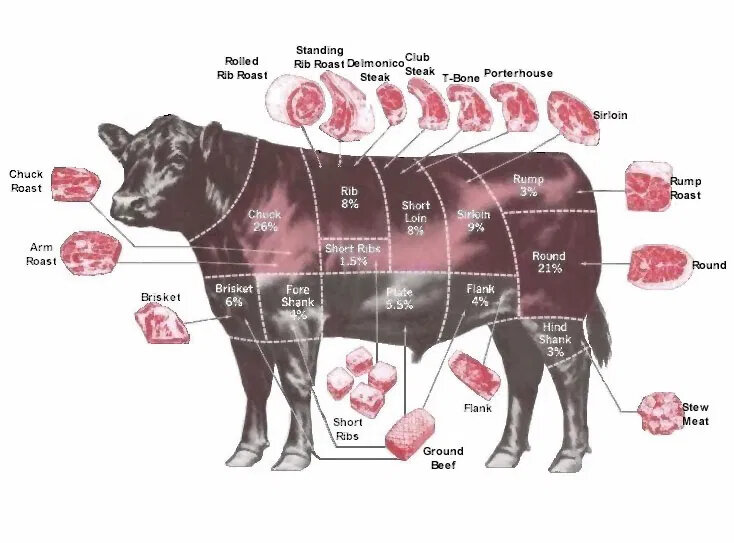

A steer's muscle meats consist of cuts like the rib eye, tenderloin, sirloin, brisket, flank, etc. You can see all those cuts and where they're found on the diagram below:

On the other hand, collagen is all the skin, bones, tendons, ligaments, blood vessels, etc., that make up the other half of the protein in the animal.

The cooked form of this collagen is called "gelatin," which I'm sure most people have heard of. Gelatin is the ingredient in Jell-O that gives it its firm, bouncy property.

While muscle meat and gelatin are both considered protein, they are quite different when we look at the specific amino acids that make up each.

Amino acids are the "building blocks" of protein. The protein in our own body is made up of 20 different amino acids. You could imagine amino acids like beads that connect to form a string. That string of amino acids is a "protein."

When you ingest food containing protein, that string of beads (amino acids) is broken down in the body. These amino acids are now in their "free state" and can travel around to do their respective jobs. Amino acids build muscles, transport nutrients, and cause chemical reactions in the body, among many other things.

Each amino acid has many different "hormone-like" functions in the body, and depending on how much of each type you consume, you can expect different health outcomes. Sometimes certain amino acids can have profound effects, even on their own.

Every amino acid is important in its own right, and while I could get into all the different jobs of each, for this article, we will stick to the ones that have the most significant impacts on our health.

Interestingly, the different amino acids found in muscle meat and the other amino acids found in gelatin can behave very differently in the body. They can be quite helpful or harmful depending on how they're combined when ingested.

Muscle meat and gelatin are two puzzle pieces that fit together and form a balance in the diet, each offering something different.

But the problem in Western culture today is that most people consume only one piece of the puzzle and need to pay more attention to the other.

Muscle meat is the piece of the puzzle that isn't in short supply in many people's diets today. On the one hand, muscle meat is a good source of protein for maintaining the structure of our body (muscle, bone, ligaments, etc.) and is a very convenient source of protein. Muscle meat is helpful during the body's time of growth in childhood and in early life, in particular, because of the amino acids tryptophan and cysteine (muscle meat doesn't contain just these two amino acids, but it does so in abundance, and I think these are the two worth focusing on in this article).

The problem is that while these amino acids are helpful in some ways, in excess and without a balance of gelatin, they are inflammatory, can downregulate the thyroid, suppress the immune system, and reduce the metabolism.

So what about gelatin?

Unlike muscle meat, gelatin is very therapeutic in many ways. But before I get to those benefits, I will explain what makes them so incredibly different.

Gelatin has an entirely different amino acid profile than muscle meat. Unlike muscle meat, gelatin contains very low levels of tryptophan and cysteine. Instead, gelatin's most abundant amino acids are glycine, alanine, proline, and hydroxyproline. These amino acids—specifically glycine—are highly anti-inflammatory and are great for thyroid health, the metabolism, the gut, digestion, and much more. Gelatin also reduces excess estrogen in the body, balances the body's hormones, alleviates insomnia, and is good for skin, hair, nails, and many other conditions associated with aging in general.

The key here is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater and avoid muscle meat altogether. Remember, muscle meat is a convenient source of protein and provides a quality protein source that helps maintain the structure of our body. The key is to consume protein in a more balanced way. Eating muscle meat with gelatin will mitigate any metabolic stress response you would get instead of eating muscle meat alone. Consuming both proteins together allows a much more balanced flow of amino acids into the bloodstream during digestion.

A super-easy way to get a healthy amount of gelatin is to consume bone broth with a meal or two during the day. It can be added to something like a soup or sauce and can be a delicious addition to a dish.

An even easier way is to get it in powdered form. Great Lakes Gelatin is the company I'm most familiar with and trust the most. Hydrolyzed collagen (the green can) and regular gelatin (the orange can) have always been well-trusted sources. The hydrolyzed collagen is easily mixable in liquid, and the traditional gelatin (the orange can) is good for baking and other food products that require cooking or heating. I will typically mix in a tablespoon or two of the hydrolyzed collagen in juice 1-2 times a day. I recommend somewhere between 2 and 4 tablespoons per day. If enough muscle meat is consumed throughout the day, it can be helpful to accompany it with 5–10 grams (1-2 teaspoons) of powdered gelatin. Doing this will do a great job of balancing the amino acids in your diet.

Common food sources of gelatin include oxtail soup, beef or lamb shank, bone broth, head cheese, drumsticks, chicken-foot soup, etc. While these items may seem unappetizing, they are usually delicious when prepared well. An adventurous spirit may need to be employed when summoning the courage to try these foods. Typically, oxtail soup, beef or lamb shank, and various bone broths are pretty palatable for most, even relatively some who are relatively picky.

Oxtail soup, don’t knock it ‘til you try it.

Many homemade treats use generous servings of gelatin in their recipes, which can be a good and plentiful source. Homemade gummy candies and homemade jello can be terrific sources of gelatin, and there are also plenty of recipes online. Plenty of healthy ingredients can be added to these recipes to make them even tastier as well.

The older one gets, the wiser it is to put more of an emphasis on dietary gelatin in the diet. Exact amounts will vary between people, but benefits will be achieved as long as there's an effort to include gelatin in your daily diet.

Regarding general protein amounts, I would advise avoiding getting too caught up in being overly meticulous in calculating and worrying about certain amounts of food but letting cravings and what you have a taste for guide your choices. If you crave steak, have the steak. Your body is probably telling you it needs a dense source of protein, and it's best to supply it with what it needs. Then add a bit of gelatin to that meal, and you're good to go.

Besides gelatinous meats, bone broths or other foods containing gelatin, milk, eggs, and shellfish can also be good options for protein, whose amino acids are a bit more balanced than those in muscle meat and don't need gelatin to balance the amino acids.

Interesting note: Whether they knew it or not, traditional cultures seemed to have figured out this balance (or maybe they couldn't afford to eat the entire animal). Traditional cultures often use the entire animal, and their dishes typically contain a much more balanced ratio of amino acids because of their use of the gelatinous parts of the animal. I've heard many stories of hunters in traditional cultures treating the lean muscle meats as scraps and often throwing them to their fellow pet hunters while favoring the organ meats and gelatinous cuts more so for themselves. Over time, Western culture has reversed its attitude toward what foods we find more appealing. In my opinion, it may be helpful to our health to try and reconnect with our earlier culinary roots that we once knew.

Links to relevant studies:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20093739

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10564180

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15331379

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=dietary%20glycine%20b

lunts%20lung%20inflammatory%20cell%20influx

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17361755

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3328957/

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161

/jaha.115.002621?sid=a00e4123-8cd2-4af1-8550-d910814acc74&